The Radical Potter Josiah Wedgwood

by Tristram Hunt

January 29, 2023

reviewed by William P. Meyers

Popular pages:

| U.S. War Against Asia |

| Fascism |

| Democratic Party |

| Republican Party |

| Natural Liberation |

The Radical Potter: The Life and Times of Josiah Wedgwood

Metropolitan Books, Henry Holt and Company

Originally published by Allen Lane, London

2021

What did it mean to be radical in the 1700s? This was before the Industrial Revolution began, before workers were molded into the Proletariat by the machinery of capitalism, before Karl Marx (born in 1818). The 1700s saw very rapid change from what was still a very much Middle Ages mentality to what we might call Modern sensibilities. Slavery was a big issue, as was universal suffrage for males, as were women's rights. In England the landed aristocracy, descendants mostly of Nordic warriors who had fought with William the Conqueror at the Battle of Hastings, were still in charge. Capitalism itself was revolutionary, as were science and rejecting the organized forms of religion.

Josiah Wedgwood was born in 1730 into a family of potters. The small family business of making crude pottery for ordinary people's use was inherited by his oldest brother. In the normal course of things Josiah would have worked in that business, making ceramics by hand, and been considered working class. Worse, infected by smallpox, he was left with a weakened knee, which was a serious disability in a time when all this work was done by human muscle. Josiah had energy and brains and started making innovations at an early age. He left his brother's business for a series of employers and then partners, until finally he was the head of his own pottery. Despite a minimal education he experimented with the chemistry of clay and glazes, always looking to create a more attractive product. Tristram Hunt's The Radical Potter traces this history in some detail. Ceramics artists and collectors will find many details of interest in this story.

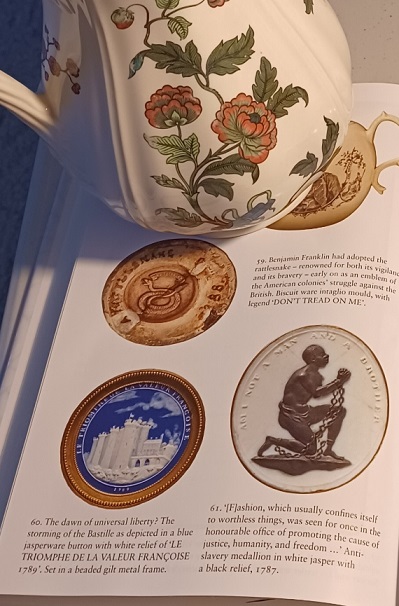

Wedgwood anti-slavery medallion, Bastille Storming, modern pitcher

It is also the story of the politics, science, philosophy and economics of the era. For me it had many useful illustrations of a theme I have been developing: that free market capitalism and the various forms of socialism are complex phenomena, highly dependent for success (or failure) on human decision making. The book talks about the Industrious Revolution preceding the Industrial Revolution. Life got better (more materially abundant) in England in the 1700s, before coal power started displacing human muscle, because people worked more and squandered less. This benefited both workers and the growing business class. Most businesses were small. In many cases, as with Josiah Wedgwood, owners worked alongside their employees. An infrastructure network was built up (by human labor) consisting of toll roads and canals. On a darker note, slavery and the slave trade contributed to capital accumulation. The book describes in some detail how owners of the slave trade and of sugar plantations in the Caribbean were able to buy luxury goods, including new, luxurious housing. As with other makers of fine goods, Josiah's clients were often these very slave owners and traders.

As he became a man of wealth and note, Josiah came to know many important people, including scientists and aristocrats, even the King and Queen. One such person was Doctor Erasmus Darwin, who became Josiah's family physician. They were both part of a science group, the Lunar Society, which also included the clergyman Joseph Priestley, discoverer of oxygen. Josiah also corresponded with Benjamin Franklin. Josiah and his circle were, for the most part, what was called English Dissenters. Josiah was, more specifically, Unitarian. At a time when the main religious rivalry in England was still Church of England versus Roman Catholics, these dissenters valued a person's personal conscience. The Unitarians denied that Jesus was god or the son of god. While the word Atheism is not used in the book, clearly the emphasis on rational thought and on inquiry into nature was taking some down the path to agnosticism or atheism.

Josiah's radicalism would not be considered very woke today. For his time it was exceptional. While he did push his workers to be industrious, he also saw to it that they had substantially better homes and incomes than they had had in the past. He supported the American Revolution, but like many enlightened English supporters of that revolution, he was disappointed that slavery was not abolished. It had been ruled abolished in England in the Somerset Decision of 1772. Yet the English did not abolish it in their colonies, nor had they yet abolished the slave trade. It took a long fight to overcome the economic interests of the English slavers. Josiah Wedgwood put considerable effort in that fight. To support it he manufactured medallions that were sold by the anti-slavery society to raise funds. The slave trade was abolished by Britain in 1807, and was made illegal in the colonies in 1833. It is this legacy of anti-slavery that earns Josiah Wedgwood the right to be called Radical in the political sense. Within the pottery trade his many innovations also earn him the right to be called a radical craftsman and even chemist.

I really enjoyed this book. It brought to light many bits of history that I was not aware of. I had only become aware of Josiah Wedgwood in the last few years because of my research into the Darwin family. Josiah's eldest daughter, Susannah, eventually married one of Erasmus Darwin's sons, Robert Waring Darwin. They moved to Shrewsbury, where Robert set up as a Doctor. Their youngest son was Charles Robert Darwin. Born in 1809, long after both his grandfathers had died, Charles would train to be a Doctor, then train to be a minister, and then apprentice as a the science officer on the famous voyage of the Beagle. Eventually he would introduce the most radical product of civilization to date, the Theory of Evolution through Natural Selection.

| Copyright 2023 William P. Meyers. All rights reserved. |